A few weeks ago, Will Godfrey (CEO, Tangible) and I co-wrote a piece titled The Rise of Production Capital. For several years, I’ve used “Production Capital” to refer to a wide and growing range of approaches for financing the emerging physical technologies aimed at transforming critical industries like energy, aerospace and defense, manufacturing, materials, and transportation.

The term is a nod to Carlota Perez’s seminal framework for understanding technological revolutions, particularly the constructive deployment “golden ages” that follow from periods of i) technological “installation” and ii) intense socio-political tension and conflict, wherein:

Constellations of convergent innovations create the building blocks that enable a new class of innovators to transform key industries.

Technology is rapidly adopted across industries, extending its reach beyond geographically limited innovation hubs to benefit a wider segment of society.

Capital flows into real businesses contributing fundamental value to the economy.

This magnitude of this deployment age is captured by BlackRock’s estimate of the impending $68 trillion global infrastructure investment boom, unfolding in an era increasingly defined by what Russell Napier calls “National Capitalism”, where state priorities reshape capital allocation toward energy security, industrial capacity, and technological sovereignty.

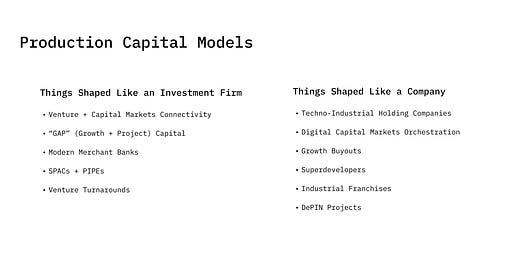

With that (still broad) framing in place, I thought it would be helpful to sketch out a mosaic of the types of firms and companies I’ve seen focused on this. The use of the term “mosaic” is intentional. This isn’t a comprehensive market map or a clean framing of the so-called “capital stack”.

The boundaries between these models are often blurry. Most are still a work in progress, not yet fully legible to the institutional capital allocation world that cements the clean lines between asset classes and financial products over the long term. These organizations are also, to lean on the scientific definition of mosaic, typically “composed of cells of two genetically different types” – founder x financier; venture x infra; physical x digital.

This entrepreneurial nature of Production Capitalists is captured well by Perez:

"Financial capital can successfully invest in a firm without much knowledge of what it does or how it does it. Its main question is potential profitability, sometimes even just the perception others may have about it. For production capital, knowledge about product, process, and markets is the very foundation of potential success."

- Carlota Perez, Technological Revolutions and Financial Capital

That these organizations transcend straightforward categorization is what creates their opportunity.

This is also an exercise to understand what I am missing. So if I have omitted categories or interesting approaches, please let me know!

Things Shaped Like an Investment Firm

Venture + Capital Markets Connectivity → “Unlock downstream financing” has always been a core VC job to be done. Diverse downstream capital needs arrive early in the physical technology company life cycle, creating an opportunity for specialist firms to earn a spot on the cap tables of the best emerging industrial companies by building a capital markets function on behalf of their portfolio. Some venture firms do this well informally, but few (none?) have developed this as a systematic platform capability. By helping founders optimize around structure, strategy, and capital markets connectivity, firms can have a substantial impact on the metrics that matter to them, like dilution over time (equity efficiency) and set companies up for more efficient subsequent financings.

“GAP” (Growth and Project) Capital → The “Compound Startup” of the Production Capital universe. Vertical integrators, building a system of capabilities that spans venture, project development, financial engineering, and industrial business development to power companies through the proverbial valley of death. The problem is abundantly obvious, but the ability to commandeer and coordinate the capital and cultural resources (i.e. world world-class talent across several disciplines from day one) to make this model a reality – as The New Industrial Corporation has done – is hyper-scarce. (h/t Will Dufton from Giant Ventures for the term GAP capital)

Modern Merchant Banks → A more flexible, “fundless” variation of the first two models, leaning into the diverse nature of capital problems to be solved inside new industrial businesses. Bespoke capital support via advisory and strategic positioning, systematic capital markets connectivity, and investment (via balance sheet or SPVs) – mirroring the way entrepreneurial financiers of previous eras built centrality during industrial shifts.

SPACs and PIPEs → Will value distribution in the new industrial ecosystem more closely resemble Silicon Valley (power law) or the German Mittelstand? If it is the latter, and if the barriers to going public remain for mid-sized companies (roughly $100m - $10b in value) we might see a revival of SPACs – ideally wielded more responsibly – to raise large amounts of capital needed for industrial scale-up, align with strategic investors, simplify access to government programs, and use public equity as M&A currency. Nuscale is a rare success story here, while blank check companies like Perimeter are emerging with this angle in mind.

Venture Turnarounds → Industrial technology scale-up and venture equity are not always perfectly compatible (as this list conveys). As more venture capital has flowed into the physical economy, more companies are finding themselves in a position with strong IP, physical assets, and commercial traction but misaligned cap tables, organizational structure, and operating models. This creates an opportunity to restructure and reaccelerate these businesses more sustainably. Jeremy Giffon discussed this on TBPN, and I am aware of a few efforts behind the scenes, but haven’t seen any public announcements.

Things Shaped More Like a Company

Techno-Industrial Holding Companies → The Outsiders of Reindustrialization, possessing the ability to systematically build, back, and buy companies and industrial assets around a core theme or “cornered resource” – Re:Build’s advanced manufacturing keiretsu, Valinor’s defense and government GTM expertise, AMCA bringing an engineering-first culture back to the aerospace supply base. As Valinor highlights in a post explaining their model, such approaches make it possible to right-size the capital and product strategy for every opportunity (i.e. not every company should be “the next Anduril” if we are to build a thriving defense-industrial base).

Digital Capital Markets Orchestration → Software and AI-enabled piping to connect institutional capital with the people putting steel in the ground (or panels on roofs), helping them execute projects more effectively, and building shared standards for new industrial finance and operations. Critically, the objective is to play an increasingly large role in capital markets transactions around projects (rather than, say, selling subscriptions), with outcome-based business models – marketplaces (e.g. Crux) or technology-enabled advisory and structuring (e.g. Tangible, Phosphor, Euclid)

Growth Buyouts → Build (software), then buy (controlling stakes in physical assets) in categories where structural inertia limits the adoption of new technology and where acquisitions offer a shortcut to vertically integrate (competing with incumbents rather than selling to them). Often a few larger assets or companies where the goal is to use software to transform the P&L rather than run a systematic roll-up strategy. Metropolis is the canonical example, but I haven’t yet seen a ton in more industrial categories. (h/t to Yoni at Slow)

Superdevelopers → Companies that build, finance, own, and operate emerging physical assets; operating as hybrids of utility, technology, project development, engineering, and financial services businesses in niche or out-of-favor areas like repurposing (Crusoe), geothermal (Fervo), nuclear (The Nuclear Company), or storage (Field, Base). As Crusoe’s $225m credit facility with Upper90 and Bees & Bears’ €500m debt commitment from a European bank highlight, many of these categories are crossing the institutional threshold.

Industrial Franchises → Great franchise models print money and have the potential to scale globally. Several extremely successful industrial and industrial-adjacent franchises already exist, from Ace Hardware to Metals Marketplace. As automation and modular hardware bring down coordination costs and improve the quality control for distributed operations (neutralizing the advantages of centralized models), franchising will become an increasingly relevant business model and capital structure for the decentralization of the real world in areas like manufacturing, energy services, waste and remediation, and industrial maintenance.

DePIN → Along the same lines of decentralization, crypto incentives pushing into the real world through distributed telecom networks (Helium), energy system redesign (Daylight, Plural Energy), positioning systems for autonomous hardware (GEODNET), and mapping infrastructure (Hivemapper). One of the most promising attributes of DePIN models is the precision capital flows it has the potential to unlock, making it possible to drive funding to smaller, niche use cases overlooked and unaddressable by centralized allocation and operational models.

Assorted Closing Thoughts

Beyond their internal “hybridity”, these models also interact with one another in complementary and sometimes competitive ways. A GAP Capital firm might provide the early funding and strategic structure that Superdevelopers need to get early projects running, while Digital Capital Markets platforms facilitate funding flows into both. In some cases, these models represent different evolutionary paths for the same company. What begins as a Digital Capital Markets company might evolve into a Techno-Industrial Holding Company as it acquires operational assets. This interactivity creates a dynamic ecosystem rather than a static landscape, with capital and expertise flowing between models as the deployment age accelerates.

There are several (crucial) categories that I know I’ve left out of this, and thus welcome feedback, corrections, and additions. Things like equipment leasing (e.g. CSC Leasing), asset-based lending (where I started my career and which I hinted at above via both Upper90 and Tangible), forward-leaning infra firms (e.g. Generate Capital), advanced market commitments (e.g.Frontier), and technology-enabled EPCs (e.g. Unlimited Industries). I’ve also omitted philanthropic, government, and strategic capital that can be instrumental in bringing additional capital and resources off the sidelines.

The Production Capital Mosaic I've sketched here represents the early architecture of models being built up to deploy trillions in capital toward industrial transformation. Whether structured as investment firms or operating companies, they share a common thread of deploying critical technologies at scale. As the multi-decade hardware and infra supercycle unfolds, we'll see further refinement (and more convergence) of these approaches, with a handful breaking through to become the Morgans, Transdigms, Drexels, Constellations, Danahers, and Berkshires of the new industrial deployment age.

Thanks to Sam Tidswell, Will Dufton, and Will Godfrey for comments on this!

You've captured a lot here. We've moved from a venture turnaround focus to venture creation in the global Creator Economy - a nascent space to keep an eye on.

Regarding "Growth Buyouts" spoke with a HealthTech founder that built a digital, remote heart monitoring solution but could not get traction and was planning to acquire some small clinics (low multiples BTW) and transform the P&L with his tech. German market....