Since I began working on Venture Desktop — and in my role as an investor at TechNexus — I've organized a lot of my research and writing around six main categories, what I think of as Economic Oceans.

These Economic Oceans — Work, Well-Being, Cities, Media, Commerce, and Industry — aren't "verticals" or trends and aren't defined by specific technologies or business models.

Instead, they are best viewed as massive pools of attention and economic value that are, to draw back to the ocean analogy, deep, complex, overlapping, and (as we are currently witnessing in real time) often quite fragile. And while the categorization is not comprehensive, we can observe that many of the most impactful companies built over the last decade — Square, Uber, Peloton, even Zoom — have been built at the intersection (and with an innate understanding) of two or three of these Economic Oceans.

Problems like climate change, as well as those exacerbated or accelerated by the Covid-19 pandemic — creaking healthcare infrastructure, supply chain instability, the mass coordination of people and ideas in a more “distant” social environment — will be best tackled by working to understand the relationships between these massive pools of activity and identifying the economic and cultural catalysts that will spur value creation within them and across them going forward.

Over time, I expect to further flesh out this Economic Oceans framework (it is very much an early work in progress).

In this essay, we will start to explore the relationship between these Economic Oceans and our current situation by highlighting three concepts — Demand Primitives, Demand Catalysts, and Spatial Economics — that may be useful to understand what types of companies and categories are best positioned to create and capture value in the future as a result of what is happening on the ground today.

As you continue reading through the post, I’d love to discuss with you here in this thread on Twitter. These ideas are a work in progress and I’d love your feedback!

Categorization and Competence

I wrote in February of this year about the merits of an entirely bottoms up approach to investing and the belief that being overly rigid in categorizing anything in investing is a great way to sound smart in the short term while losing money in the long term by blinding yourself to emergent opportunities.

I also believe that seeking to dynamically define and understand the limits of your own analytical capabilities (and interests) is paramount. This, of course, is Buffett’s circle of competence.

What an investor needs is the ability to correctly evaluate selected businesses. Note that word “selected”: You don’t have to be an expert on every company, or even many. You only have to be able to evaluate companies within your circle of competence. The size of that circle is not very important; knowing its boundaries, however, is vital.

These two principles are not at odds. Investing (and before that analyzing companies) effectively that fall within one’s circle of competence — even as a true expert in that circle — does not imply playing the “greater genius” game of predicting the future.

Perhaps by definition, the most innovative companies transcend traditional categorization by bundling emerging technologies, new business models, and new user behaviors in novel ways. Alongside this, companies are attacking increasingly large markets earlier in their lifecycle and blurring competitive, geographic, and business model lines in the process.

The complexity of these interactions, coupled with macroeconomic factors outside any one company’s control, have a way of rendering even the most cogently developed predictions about the future largely inaccurate.

Demand Primitives and Catalysts

One way to solve for the challenge of predicting the future in markets dominated by uncertainty is by anchoring on demand. This is true both for investors and for operators. And while the idea of demand-driven innovation runs slightly (though not entirely) counter to the Henry Ford or Steve Jobs “faster horses” approach, it tends to be the direction the pendulum swings during periods of depressed capital availability.

The Economic Oceans I highlighted at the top, in up or down markets, represent some of the largest pools of demand in the entire economy.

But while understanding existing demand is important, it is not sufficient to develop a differentiated (or non-consensus) perspective on how to map the situation on the ground to what may unfold in the future.

To take the next step and figure out where non-obvious demand is hiding, it helps to identify and understand two additional factors.

Demand Primitives — Where is high “engagement” already observable but significantly under-monetized or effectively monetized but in narrow segment of a broader market?

Demand Catalysts — What cultural, economic, and technical shifts (already in-flight) will make it possible to bundle multiple demand primitives to build companies that create entirely new categories?

It may be a subtle distinction, but I believe the framing of what is happening (engagement) and what could happen (catalysts) vs. what should happen (intellectualization) helps those analyzing companies or operating them stay grounded in the tactile reality of the market instead of becoming overly dependent on narratives, trends, and abstract concepts that don’t square with real needs.

Another way to think of this is that a company’s Demand Primitives comprise its “secret” while the Catalysts help to answer the question of “why now?”.

Our Pulled Forward Future

Never before has the why now (or why never) question been so straightforward to answer for so many companies.

The bundling of Demand Primitives and their interaction with Demand Catalysts typically happens over the course of years. Entrepreneurs and investors try to suss out how the underlying engagement present in a set of Demand Primitives can be brought together on a time horizon that allows a company to benefit most from the onset of key Demand Catalysts.

Covid-19 has pushed this interaction to the poles. For certain categories, catalysts that would have taken years have hit with full force arrived in a matter of weeks. For other companies and categories, the onset of any positive catalyst has been pushed out well beyond the range of solvency.

Gaming, online education, distributed work, at-home wellness, and urban delivery were already significant and growing quickly before Covid-19 but each has had its near term TAM curve tilted straight upwards.

Thus far, we are seeing in-flight behavioral and cultural inevitabilities "pulled forward" significantly more than we are seeing the creation of entirely new behaviors.

There is a compounding effect to this as well, with the “winners” of the current paradigm in each of those categories mentioned above being forced to aggressively invest in R&D and Capex simply to keep up with exploding demand.

Not every company or category benefitting in the near term will see its success persist, just like many areas currently being crushed will bounce back in due time. As Alex Danco points out in a recent post, positional scarcity ensures things like business travel and top tier university educations will retain much of their previous importance.

First, let’s take business travel. Getting on the plane means you’re serious about something. Everybody’s busy; the fact that I’m choosing your one hour in person rather than an entire day of otherwise productive work is a signal: “I’m taking this seriously.” It establishes a concept of "place in line”, with this meeting being at the top.

That kind of commitment is often necessary for everyone involved to prioritize this meeting, and its action items, high enough on their to-do list that things actually get done. You have to take the time and expense to physically situate yourself there, in close enough proximity. Positional scarcity is a zero-sum game, and it’s something we can purchase with our money and effort. The more costly it was to get yourself there, arguably the better. If you don’t take the time to fly over, by the way, you risk being bumped down the priority list in favour of the people who do.

Higher education works in a similar way, although at higher stakes and over a longer time scale…

I agree with this and recommend reading the full post. Like all of Alex’s work, it it outstanding.

But what about the marginal business trip? Or a state’s 5th best public university? Or the one or two days per week that employee doesn’t need to engage in “expensive” signaling by showing up to the office in a suit to met with clients?

The Economics of Distance

While positional scarcity will help certain companies, institutions, and activities — those that confer legitimacy and prestige or benefit from temporarily disrupted network effects — rebound with resilience over time, there is a high probability of a structural reset in the scrutiny we place on many non-essential and even borderline essential activities and institutions.

This goes well beyond the near term health concerns related to the virus or the demand slowdown in many areas. Underlying these “forced” factors is something much more significant — sort of a Meta-Demand Catalyst that will persist much longer than direct concerns about Covid-19 or a recession:

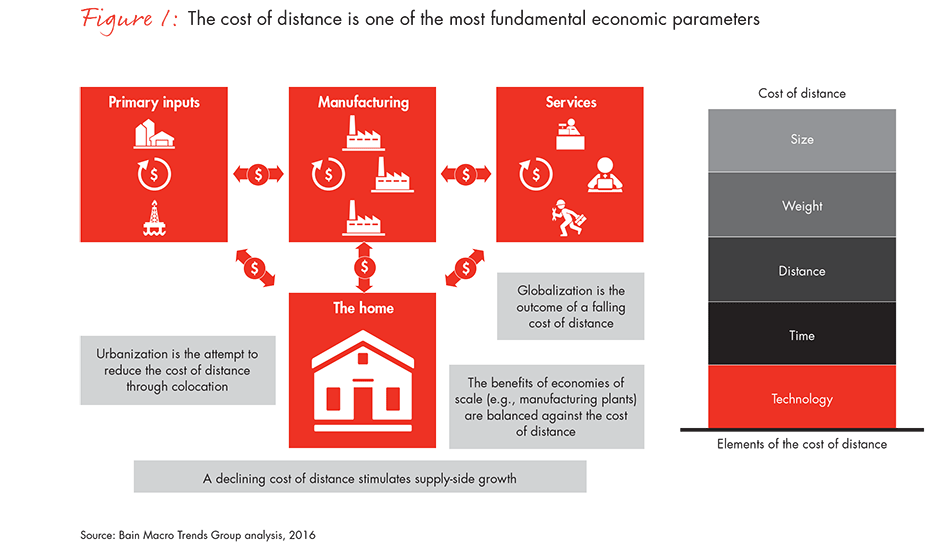

We are seeing for first time an economic shock create a discontinuous divergence in the spatial economics (the “cost of distance”) between the physical and digital worlds.

Over the past few decades, we have witnessed a broad-based decline in the cost of distance across both the digital and physical worlds. But while the digital cost of distance has fallen at a much faster rate, the relative decline has not been significant enough to break the status quo bias that has kept many things functioning as they always have.

As the relative cost of distance has rapidly decoupled, long-held beliefs about “how things are done here” — from health to education to business — are breaking down and having a significant impact on near term capital and attention flows. The contrast between the recent debt raises from Slack (positive spatial economic impact) and Airbnb (negative) illustrate this well.

Demand, Distance, and Economic Oceans

Taken together, we can start to piece together a framework to assess the relative strength of companies based on the degree to which they possess positional scarcity and the positive or negative impact of this rapid Spatial Economic shift on their business.

Companies that have thrived over the last decade have natively grasped the complexity of operating in a world defined by Economic Oceans and tend to possess two primary characteristics:

Internalization of the tactile realities of multiple Economic Oceans

Resiliency (even Antifragility) in the face of shifts in Spatial Economics

Taken together, this makes it possible for these companies to dynamically bundle a unique set of Demand Primitives in order benefit from positive catalysts or persevere if the why now? gets pushed a few quarters into the future.

Most of the companies that embody these characteristics will experience “Resilient Recovery” (Airbnb) or take advantage of “Obvious Growth” (Slack). A select few — those who can both internalize the relationships between intersecting Economic Oceans and are antifragile to changing costs of distance (Square is one I have in mind) — will enter the top right quadrant and create entirely unforeseen value in the wake of this economic reshuffling.

This was a long post and I appreciate you reading this far! If you made it here, I imagine you either loved the post or hated it! Either way, I’d love to have you share it and come discuss with me on Twitter. You can also shoot me an email if you have feedback or want to discuss!