A conversation with Paul Murphy, General Partner at Northzone

Founding Dots, backing Hopin and TIER, and what it is like to work with Tencent

Last week, two of Paul Murphy’s portfolio companies – Hopin and TIER – announced that they had surpassed billion dollar valuations on the exact same day.

As rare as that may be, it isn’t the least bit surprising. Paul represents the best of the new wave of early stage investors in Europe – product minded, deep operational experience, and a global perspective on company building.

I was lucky to sit down with Paul to discuss what he has learned from the rapid rise of those two emerging European champions and so much more. I learned a ton and hope you will as well.

You can read the highlights and key takeaways of our conversation below or listen to the discussion on Spotify, Apple, or wherever you get your audio content. You can also come discuss the conversation on Twitter.

I want to give a huge shout out to Vincent, Paul’s colleague at Northzone, for helping make this happen!

What we discussed

The role India played in shaping Paul’s international perspective

Betaworks and the early days of Dots and Giphy

Trying (and failing) to conquer the Chinese gaming market

Tencent, strategic capital, and “hiring” your investors

What makes a great VC and what he focuses on at Northzone

Lessons from the rise of TIER and Hopin

On how India shaped his international perspective

“You have to build something that you intuitively understand.”

Brett: Something that seems to tie your career together – from Microsoft, to Dots, to Northzone – is a deep desire to understand how all of the pieces around technology and culture and business are intersecting at a global level. I thought we could start to try to get a sense for where that curiosity came from. In the early days, what experiences shaped that international perspective you have?

Paul: First off, great to be here, thanks for having me on. When I initially joined Microsoft, I had just come out of a startup that I co founded. We scaled up and then we had to lay everyone off, shut it down. We sold it for parts and it was really painful. I was very young, I didn't really know what I was doing.

At Microsoft I started learning about how a big company operates and I got pretty bored of it. So I used my time at Microsoft as an opportunity to move around the world. I spent a couple years in London, and then I spent just over a year in India.

And it was that time in India when I saw all of these incredibly talented engineers, designers, product people, building products for the West, and not their local markets. That was just so odd to me, I couldn't understand why you'd build a product for someone else. As I was there, a lot of that was starting to change. You saw the growth of these local entrepreneurs that were building products in India for India.

And that's kind of when it clicked for me that if you're going to build something, you have to build something that you intuitively understand. So that's been the thread, since I left Microsoft. I'm always looking for founders that really understand a core problem and are trying to solve that problem.

Brett: I would echo your, your thoughts on India. I lived there for a year during the rise of Flipkart and you could just kind of see the switch get flipped and the light bulb go on for so many entrepreneurs there.

On Betaworks and the early days of Dots

Brett: You hit on an interesting point about the importance of building for problems you understand. That’s a good transition to talk about what you did next, spending time at Betaworks and eventually founding Dots. How did all of the founding ingredients come together for that company?

Paul: It's hard to talk about Dots without giving the context of the environment that was built – which was Betaworks. Betaworks had been invested and building in New York for years before I got there – they were a part or some of the city’s really big early successes like Tumblr and Kickstarter.

I came in and helped create a new wave of companies at Betaworks. The first thing we did was we shut down a bunch of stuff that was kind of okay, but not great. Then recruited in a group of really impressive people – hackers, creatives, sort of these polymaths that could build, design, and understood product. There were eight of those individuals and me.

We had three months to see what we could accomplish, and so all eight people began tackling different problems. I found myself hopping from idea to idea, helping people pull together common threads. And then increasingly, what happened was those people started feeding each other ideas and giving each other feedback.

It was a really special environment, I don't think that those eight individuals would have necessarily been funded by angel investors or seed investors. But the Betaworks environment allowed for them just to experiment for a couple months.

Brett: And out of that came Dots?

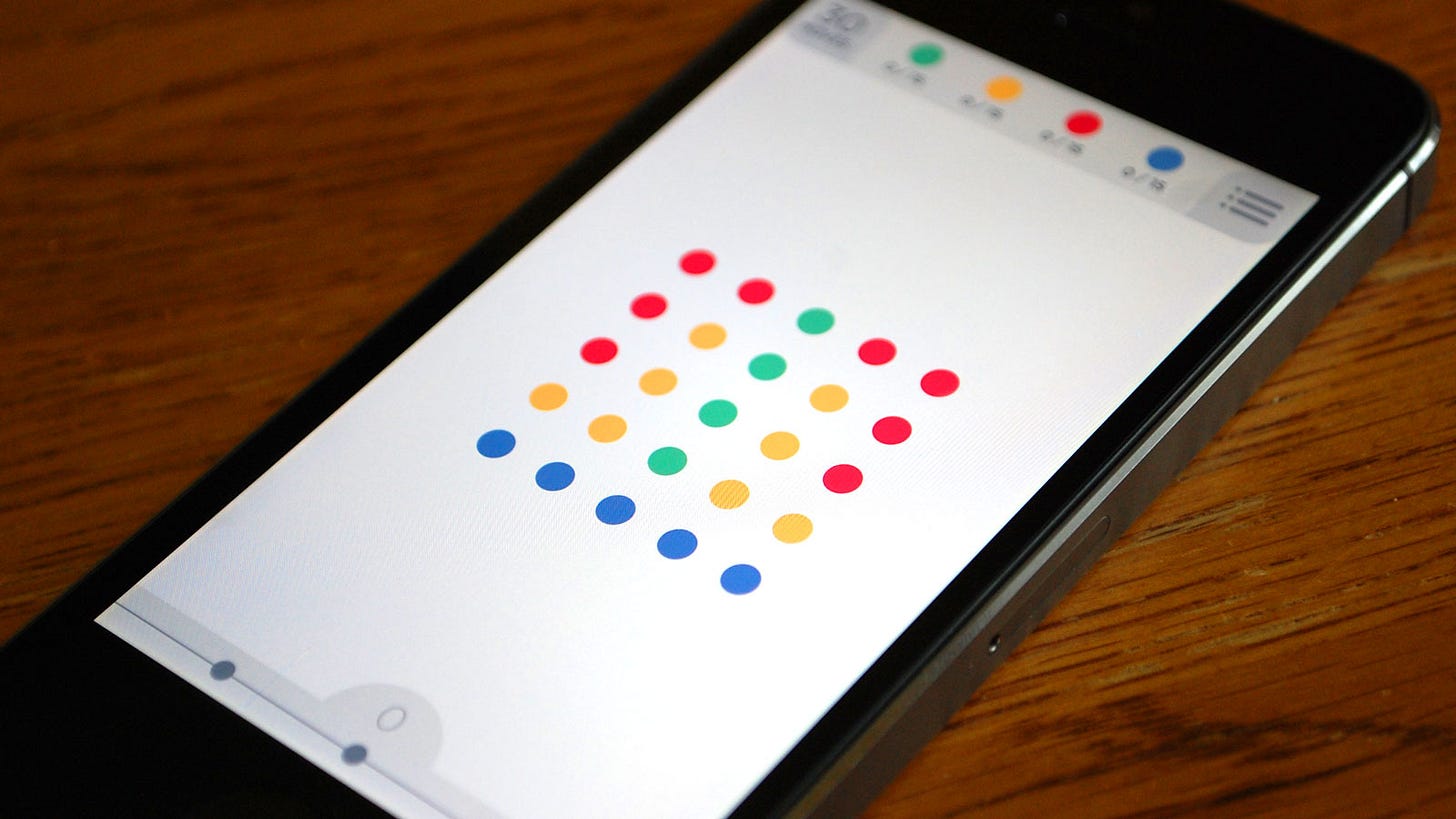

It was Patrick [Moberg], who built the first Dots game. He said:

I love design, I care a lot about every aspect of design in my life. And I love games. But when I want to play a game on my phone, I'm forced to play these games that look like they are casino games or made for kids. Why isn't there something that looks like everything else looks in my life?

We didn't know how big the opportunity was at first was. We knew at the very least there were thousands of people who this would appeal to.

But when we launched it, we realized, okay, there are millions and millions of people that actually want something like this. So it started from a very authentic place – I want to build something for me and my friends.

In that same time period, we did exactly the same thing with Giphy. We found ourselves going to Tumblr pages, looking for gifs, trying to find the best secret Tumblr gif pages. But it shouldn’t have been that difficult. Why was that tribal knowledge, that experience that should be accessible to everyone hidden? And so it was the same way we started that company.

On entering China

“If I want to build the next great gaming company, I have to be in China.”

Brett: Dots was pretty much a global phenomenon right out of the gate. I remember seeing that within 24 hours of launch of version two of the product, you shot up to number one on the App Store charts in 71 different countries. But there was one country you still hadn’t conquered: China. What drew you to that market?

Paul: In 2014, unlike almost every other sector, China was the biggest market in the world in gaming. It wasn't the US, it wasn't Europe, it was China. And mobile gaming specifically was massive – one of the reasons is that consoles were banned until I think it was 2011. So there's a whole generation of gamers that grew up and the only way they knew how to play games on their phone.

There was a level of sort of sophistication – the willingness to pay, the amount of time consumers were willing to spend in a game on a mobile phone in China was just so much higher, and it was so much more advanced than anywhere else in the world. It created a really, really big market. It's big and it's going continue to grow.

At the same time. every publisher in China was coming after us saying, “your game is so different. It's so fresh, we think it could actually appeal to more of the white collar worker in China.”

So we pretty early on started talking all these different publishers and thinking maybe we can do something really different because even the best game studios in the West struggled to launch in China. King struggled. Supercell eventually had some success, but they struggled for a while.

Brett: What was behind those behind the struggles of those companies? They certainly didn’t lack resources or motivation.

Paul: One is the the difficulty curve of a game needs to be different. In western markets, we might onboard someone over the course of two or three days, or five or six hours of gameplay. In China, you know, you have to make that happen much faster, because they are much more savvy on mobile gameplay.

Then you also have to be more mindful of how you when you pinch people at different levels in the game, and to get them to monetize. The approach to pinching users at different points in the game is different. Tolerance for ads is different. The list goes on and on.

The best games are designed with monetization in mind from the outset. By trying to retrofit it for another market, you lose something in the process. We we definitely did. I think those those other companies did as well.

What ends up happening almost every time is, you give the game to your partner in China. – for us it was Alibaba then Tencent. They give you all this feedback then they make changes directly. When it comes back to you, it is unrecognizable. you don't recognize it. It's not your game at all. But you sort of say, “ok, I trust you, let's launch it.” And it usually doesn't succeed.

On why Dots failed to take off in China

Brett: Were you in a position at that point where you were adjusting your org structure, your team, your product priorities to to make the product work in China?

Paul: We wanted to have our hand in the game design for China. So we actually started recruiting Chinese speaking designers and engineers to work with us in New York. And the reason for that is that there was like 30 different payment platforms, 30 different app stores in China you had to build your game for. And all of the documentation was in Chinese. So our developers couldn't work with it.

So we had to hire Chinese speaking, developers and designers. And what they would have midnight calls with the teams at Alibaba and Tencent. We had a team of about six people on Dots for China for about a year. It was a pretty significant investment. Then we launched and we quickly could tell that it wasn't going to be a big hit in China. It was it was a real letdown, but I'm glad that we gave it a shot.

Brett: How much of that failure came down to your own mistakes vs. factors that were outside your control?

Paul: I've thought about this a lot. To me, it comes back to that point that we mentioned at the start of this chat – we were foreign developers trying to build a game for market that we didn't understand. It didn't matter how much input we got, we just didn't understand the market.

What I would have done in retrospect is I would have said, Let's build a studio in Shanghai or Beijing or somewhere where we can get great local talent, have that talent come spend a couple months with us in New York to understand what it is that we're trying to build, and then let that team go off and build games for the Chinese market. They would be doing it from a place of local knowledge and authenticity. That would have been a smarter, better investment.

Brett Bivens: Right, more of a hub and spoke model – or at least a more decentralized model to push some of the some of the influence around product decisions out to the out to the edges in the individual markets.

Paul: Exactly. Our whole thing was, we wanted to make beautiful games. It was a pretty simple mission. And we could have executed on that with phenomenal designers in China. We could have executed on that anywhere in the world. It didn't have to be out of New York.

On Tencent, strategic capital, and “hiring” your investors

“Tencent knew things about our game that we didn’t even know.”

Brett: You mentioned Tencent. They have grown into this massive gaming company and one of the most successful venture investing organizations in the world. How did that how did that relationship come about?

Paul: They have a team of analysts that track the app stores all over the world. They initially approached us when we were in soft launch – we hadn't actually launched the game properly. We were only in Australia but they could see the game was performing well. What is funny is that they clearly had much better data science at the time that we did. They knew things about our game that we didn't yet know

I flew out to Shanghai and got to meet the senior team, specifically Dan Brody. Dan is an American who is also very much Chinese. He's been living there for a long time speaks perfect Chinese And I formed a great relationship with him.

He knew so much about the gaming industry, that I felt like if there was ever a way to work with Tencent, I'd be foolish not to.

Then they asked if they could publish our game in China, which coincided with our Series A process. We wanted a more standard VC driving terms for our series A so we also brought in Greycroft to lead along with Tencent.

Northzone also came into that round. Our thinking there was, let's get the best ambassadors for Asia, Europe, and the US that understood gaming. All three fit the bill.

Brett: You mentioned Tencent’s global data science team. What sort of what value did that create for the company post-investment?

Paul: The access that we were given was shocking. We would send them builds of our games and we would get these detailed reports back from their teams telling us all the things that we would change if we were building this game, because they have the both the studio and a publishing arm.

Because of their global focus, most of the input we got from Tencent was not even for China, it was most of it was our main markets.

All roads in gaming lead back to Tencent. They would host these events where they bring their portfolio companies together – you’re sitting next to the CEO of Epic Games, people from Activision, Supercell. You had the best minds in the industry, so if Tencent couldn’t answer a question then other people that could.

On what to look for in strategic investors

“Strategic investors are dangerous territory for most startups, but Tencent was the exception.”

Brett: What should startups try to test for in a strategic partnership and a strategic investment relationship, in advance of, of taking the investment?

Paul: The biggest thing is understanding their interest and incentives around driving strategic and financial returns. I do think the interest should be financial. Tencent’s was.

That's important, because it means you're not going to experience any funny business as your as your company grows and exits. When we started discussions with Take-Two (the eventual acquirer of Dots), Tencent was very clear that they wanted to be a supportive investor and let that process run its course without interfering.

Not every strategic investor has that mindset. Others might have had ROFRs, pushed for preferential terms in an exit, or done any number of other things to stand in the way. You want to ensure that working with this investor isn’t going to prohibit you from going after business in the way that is best for the company. For example, is having them on a cap table going to create channel conflict or partner conflict?

If the answer is no, and they know a lot about your industry, and feel good about the relationship with the people – as we did with Dan and Ben Fetter at Tencent – it is worth exploring. In some ways, the same rules apply for strategics as they do for a traditional VC.

On joining Northzone

“The first company I invested was a gaming company, then it was a direct consumer health company, then it was a mobility company, and then a B2B SaaS company.

So there's not like a ton of overlap in terms of theme, audience or market. What has been the case in every company that I ultimately invested in is that I've fallen in love with the founders and fallen in love with the product.”

Brett: After Dots, you joined Northzone as an investor. How did that come about?

Paul: I think the core value of a great investor – and I experienced this as a founder – is that they are someone a founder can call nights, weekends, and just vent. The reality is when you're running a company, you have no one else to talk to.

Having someone that's got enough experience, that's always available for you, and can help walk you through difficult situations. To me, that's number one.

The team at Northzone embodied that approach.

So when I was moving to London and looking at what to do next, Northzone was the firm that I had the most experience with in Europe. But I still spent seven months getting to know the rest of the team better and making sure it was the right place for me.

Brett: How would you describe the Northzone strategy?

Paul: Northzone is one of Europe's oldest funds. We started in 1996, the same year as Index and Partech. We initially started in Norway, then expanded across the Nordics and over a decade ago moved into London. Now it's a pan-European fund with a presence in New York. We we want to see every great company that comes out of Europe. That's our, our home turf.

In terms of sectors and stage, we love to invest early. Four of the five GP are former founders, which is not necessarily unique in the US but is very unique in Europe. We're comfortable making that early bet when we see great founders and great products. Our latest fund is a $500 million fund.

Brett: And within that, how do you define your own personal investing strategy?

Paul: The first company I invested was a gaming company, then it was a direct consumer health company, then it was a mobility company, and then a B2B SaaS company. So there's not like a ton of overlap in terms of theme, audience or market. What has been the case in every company that I ultimately invested in is that I've fallen in love with the founders and fallen in love with the product.

So for me it is about the founder and product.

On TIER, Hopin, and different approaches to international expansion

TIER: Market by market

“TIER stayed very focused on being an operational machine while the rest of the market was basically trying to brag about how much capital they raised.”

Brett: I’d love to transition to talking about a few of your investments more specifically. Let’s start with TIER and micromobility. We share the perspective that micromobility is much broader than just scooters, that it is really about a redefinition of transportation inside of cities and reshaping the cities that we live in. What attracted you to TIER, what has that growth trajectory been like, and how have they approached international expansion?

Paul: I think TIER is the only company at scale in the shared miromobilty space that hasn’t done a down round. They are such a strong operational machine.

Going back to the previous point, when we invested, I think there was five people at the company and they hadn't launched anything yet. But their vision for helping ease congestion, combating pollution, and helping cities was authentic. That was truly unique relative to other companies we saw.

We had high conviction in the market – that all of our cities are broken. We didn't need to be convinced there. They had a clear vision driven by real strong purpose. That purpose was evident to cities and politicians as well. Those people were frustrated that previous mobility operators didn't engage with them and they were open to engaging.

TIER stayed very focused on being an operational machine while the rest of the market was basically trying to brag about how much capital they raised. They took the opposite approach and said, if we have to raise a lot of capital, we failed. And so how can we get the most out of this? How can we sweat every asset as long as possible? How can we be the best on the ground in each local European market we enter?

Brett: You talked earlier about how if you were building Dots again, you would go all on building a team in China. It is interesting to see that same approach now come full circle with how TIER approaches growth.

Paul: In the case of TIER, they would not settle for anyone but the best person that local market. When I looked at some of the competitors in the space, they might ship someone over from the headquarters in the US or some other place. And that person is probably incredible talented, but it is such a local business and they didn't have that all that local market knowledge and context.

Hopin: Global from day one

Brett: And Hopin has a different approach. Much more product led, less need to have a footprint everywhere they are active.

Paul: They have been going after a global market since day one. They don't have the luxury of going kind of country by country, because they have to be in every country from the outset.

The global from day one mindset is something Northzone is very familiar with. As my partners have said, that', because in the Nordics, you can't afford to think about your local market as being interesting or the end game. Spotify thought global from day one. iZettle, same thing. That approach is not right for everyone, but for a company like Hopin that approach is critical.

Thanks so much for reading. I hope you learned as much from this as I did. As a reminder, you listen to the discussion on Spotify, Apple, or wherever you get your audio content.

I would love to have you share this post with your colleagues or come discuss with me on Twitter!