This post is co-authored with William Godfrey, CEO of Tangible, which builds technical infrastructure for sustainable asset-based lending.

"Decades from now, we might reflect on 2025 as another pivotal moment, when the financial landscape shifted once again."

- Larry Fink, BlackRock

The structure of the global financial architecture is set in stone – until suddenly it isn't. Financial history is marked by the redrawing of asset class boundaries by breakthrough companies, creative financiers, and macroeconomic shifts. This often happens at a shocking speed.

In these moments of transition, institutional capital often convinces itself that it's still operating in a previous paradigm long after that moment has passed. Today, the paradigm around which much of the asset management industry is oriented – the era of globalization and unobstructed capital flows – is rapidly giving way to what Russell Napier calls "National Capitalism," where state priorities around energy security, industrial capacity, and technological sovereignty reshape capital allocation.

Over the last few years, venture capital has had its guard up about the threat of AI enabling the proverbial “one-person, billion-dollar company” – small teams leveraging AI to create massive value without the need for massive amounts of venture funding.

Slightly more behind the scenes, another fundamental force is reshaping how technology scales in this new economic paradigm, putting pressure on the traditional venture capital model: debt.

From transport fleets (Zenobē) to digital infrastructure (CoreWeave) to energy storage (Base) to manufacturing (Hadrian) to clean fuels (Twelve) to aerospace (ISAR) – debt is playing an increasingly key role in the capital stacks of the most promising emerging companies. For companies deploying valuable hard assets – batteries, modular robotics, CNC machines – asset-based lending is emerging as the wedge to unlock scalable project and equipment-level finance, allowing these companies to grow at venture speed while consuming far less equity capital.

These hard asset businesses are increasingly built and valued on bundles of cash flows rather than revenue multiples, requiring an entirely different approach to capital formation across the company lifecycle. And while several early movers have begun to break through, the holistic financing models best suited to systematically support and scale this model remain fragmented and underdeveloped.

The most valuable financial innovations that grow out of this era will mirror the significance of this macro wave and the ambitions of the companies riding it, not merely creating efficiencies or engineering marginal returns, but fundamentally realigning incentives and reducing friction in capital formation to address these new structural realities.

The $68 Trillion Opportunity

As Larry Fink highlighted in his recent Chairman’s Letter, we are approaching an infrastructure investment boom of staggering proportions.

“Today, we're standing at the edge of an opportunity so vast it's almost hard to grasp. By 2040, the global demand for new infrastructure investment is $68 trillion. To put that price tag in perspective, it’s roughly the equivalent of building the entire Interstate Highway System and the Transcontinental Railroad, start to finish, every six weeks – for the next 15 years.”

Along with these figures, he posed a crucial question: "Who will own it?"

The obvious answer might be the world’s mega-credit funds, today sitting on hundreds of billions of dollars of dry powder and seeking to move up the risk curve as margin in established categories is competed away.

They recognize that deploying $68 trillion to drive true economic growth and renewal will require investment in new infrastructure categories – next-generation energy systems like modular nuclear and grid-scale storage, advanced manufacturing facilities for critical components, novel materials production, and autonomous logistics networks, among others.

The challenge isn't one of capital demand. It is a supply-side bottleneck. Simply, there are not enough investment-ready companies, assets, and projects with institutional-grade scale and risk profiles in these new segments.

While credit funds want to move earlier in the technology lifecycle and into new categories, they lack the agility and capacity to unlock this bottleneck. Their investment mandates, governance structures, and operational processes are fully optimized around mature assets with established cash flows, not emerging technologies at the point of commercialization.

Similarly, the venture capital ecosystem, where most of these emerging hard asset categories get their start, has thus far proven unprepared and undertooled for the debt-dominated, project-centric scaling model required of the physical technology companies that will define the coming hard asset supercycle.

As such, the greatest opportunity in this supercycle exists for an emerging class of "Production Capitalists."

That is, firms with a mix of venture and credit DNA that can i) identify and back emerging companies turning breakthrough technology and novel business models into the critical infrastructure powering energy transition, reindustrialization, and security initiatives, and ii) play an active role in helping those companies build the financial foundation – construct their capital stack – to unlock efficient scale.

These firms manufacture their own alpha by building the connective tissue between early-stage innovation and the mainstream credit, infrastructure, and strategic industrial capital that can scale it. They are purpose-built to coordinate efficient capital-intensive deployment on behalf of their companies in the emerging National Capitalism paradigm.

They operate less as investors and more as builders. Their “product”, which they co-develop alongside the technology companies they back, is a scalable bundle of infrastructure-ready projects and physical assets.

The Capital Orchestration Gap

A core function of venture capital has always been organizing downstream financing. However, as hardware and emerging industrial technologies comprise a larger portion of venture portfolios, this takes on a new meaning and importance.

Today, the capital stack of most emerging hardware companies remains fragmented, poorly sequenced, and lacking efficient integration of debt and equity components.

Most emerging hardware companies – built by technologists rather than financial engineers – struggle to navigate debt markets independently early in the company life cycle.

As a result, these businesses lack proper leverage, with equity inefficiently deployed on hardware assets when better financial structures exist.

In this process, the transaction costs for raising debt are prohibitively high for early-stage companies, not because business fundamentals can't support blended capital, but because expertise and relationships aren't developed.

These factors, which now arise earlier in the company lifecycle, can create a persistent drag on growth, slowing down technology deployment precisely at a moment where demand from urgent buyers is creating unprecedented revenue opportunities. To borrow a point from the Blackrock letter referenced earlier, the current model for financing hard asset technology businesses can be summed up as abundant capital, deployed too narrowly.

So, what does a less “narrow” model of capital stack development look like for these companies? And what role does that create for the Production Capitalists backing them?

Optimally constructed, the progression often looks something like initial venture equity for R&D and product development, followed by targeted asset-based debt that serves as a wedge to unlock project-level financing once the core technology demonstrates commercial viability. As deployment scales, warehouse facilities or securitization structures become critical to efficiently finance multiple deployments simultaneously, allowing companies to recycle capital without returning to the venture markets. These securitization structures transform illiquid hardware assets into tradable securities with predictable cash flows, dramatically expanding the pool of available capital beyond traditional venture sources.

As Will wrote in an earlier piece on crossing the hardware valley of death, financial mastery is a necessary condition for great industrial businesses:

Look at any successful hardware company and you'll see the same pattern: they evolved from pure manufacturers into financial powerhouses. Tesla isn't just a car company - it's one of America's largest consumer lenders. John Deere, Siemens, and ABB all built their own banks.

This financial maturity isn't optional. When you master the capital stack, you don't just attract debt; you make your equity story more powerful. Investors back you because they can see exactly how their risk capital gets amplified.

Closing this orchestration gap for companies and capturing the hardware supercycle opportunity thus requires a retooled and more expansive approach from investors. It means becoming both active company builders and sophisticated financiers rather than VCs.

The best VCs have traditionally excelled in helping founders understand “what great looks like” for the upcoming stages of their business. Doing that for hard asset, emerging industrial companies requires an evolved set of capabilities:

Structured Finance Expertise: Understanding asset-backed security terms, project finance structures, and the nuances of debt covenants

Debt Provider Networks: Building persistent relationships with debt providers that transcend individual portfolio companies, creating soft credit enhancement through trusted relationships

Sequencing Mastery: Orchestrating the timing between equity and debt raises to optimize capital efficiency and valuations

Market Readiness Support: Preparing companies' operations and receivables to be ready for institutional funding, a perfect fit for the typical 12-24 month cycle within which VCs typically engage between funding rounds.

Counterparty Networks: Any institutional financing brings with it a supporting cast of critical actors – reporting, servicers, and offtakers, among others. Building expertise and redundancy across this set of functions (by, for example, working with Tangible 😉) is a critical risk management function to avoid delays and missed opportunity windows.

Venture investing is the art of the possible, debt financing is the science of statistical certainty.

This requires an uncomfortable grappling by founder and investor alike of all the uncomfortable possible downside scenarios. It requires understanding and weighing all the risks of the trade – financial model, data, contracts, market outlook, and operational contingencies for every conceivable scenario – and conveying those credibly to debt providers.

It requires internalizing the incentives of debt providers. Lenders want to know that borrowers fully understand how their product works. That you feel their presence in the room when offering a customer split payments, a subscription, or a lease. They are, after all, the second customer hard asset businesses must design for.

The inherent divergence of this approach from the status quo inevitably favors new firms purpose-built for the opportunity – most existing firms will be caught in the middle of this transition, lacking either scale or agility.

The active, entrepreneurial investors who master these capabilities will gain substantial competitive advantages. By orchestrating capital formation, they free up resources at the company level to focus on technology development, unlocking the speed needed to be first to massive pools of urgent demand opening up constantly across key industrial categories. And by being deep in the details of company building, they position themselves, both informationally and relationship-wise, to eventually participate across the capital stack and across the company lifecycle in the most consequential companies of this era.

Seizing the Means of Production (Capital)

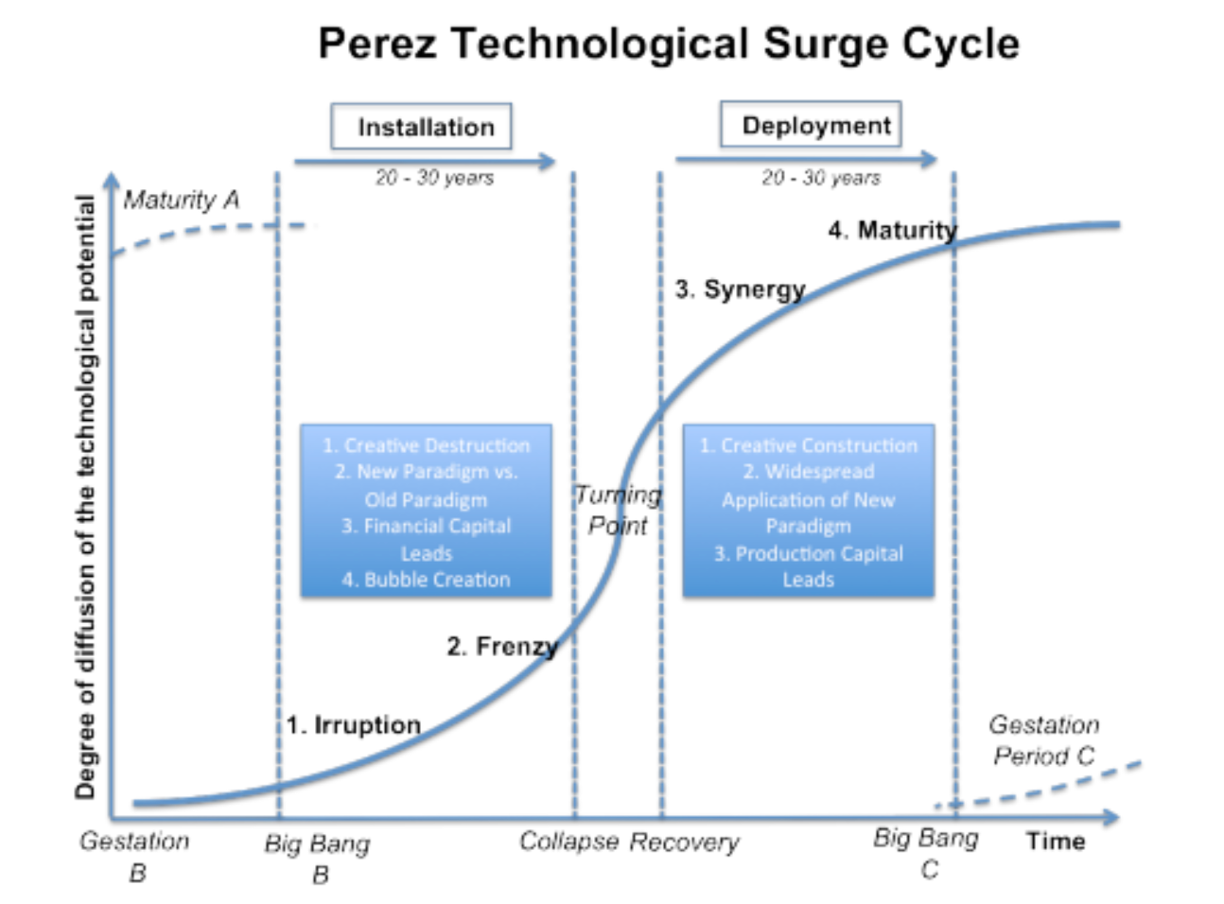

The capabilities underpinning the Production Capital model represent more than an incremental evolution – far more significant than, for example, the rise of “VC platform” teams last decade. They are the starting point for a fundamental reorientation of the “continuum” of private capital in response to a structural shift from technology installation to an age of deployment.

For venture firms looking to develop these capabilities, the starting point is straightforward (though not easy): invest in building relationships with existing capital markets players, understand the mechanics of asset-backed financing and project execution, and invest in talent with structured finance expertise and project development experience.

The even greater challenge comes in bridging these two worlds under one roof – the venture market dreamers and the credit market pragmatists – to create not just unique positioning but an integrated capacity to transform how emerging industrial technology scales.

The answer to Larry Fink's question of "who will own" the $68 trillion infrastructure boom will increasingly include Production Capitalists and the companies they finance and shape.

By removing transaction costs, unlocking information asymmetries, and reducing friction from the capital formation process, these firms will accelerate the deployment of critical technologies at precisely the moment when speed of implementation matters most, and where existing financiers will prove unable to cope in the face of increasing complexity.

The firms that successfully embrace this capital orchestration role will not only generate superior returns by manufacturing their own alpha, but they will also become critical enablers of the infrastructure revolution essential for driving the next era of economic growth and competitiveness in Western economies.

Super interesting. Came here from "Expotential View". I completely agree with the thesis.

Debt is a critical part of growing the "hard companies". We need either a rapid evolution of VCs from SAAS players to Production Capitalists.

Amazon has raised approximately 7x more capital through debt ($67B) than equity ($9.3B) over its lifetime. But that hides the billions it self financed since 2000s through its own cashflow.

This is a brilliantly written piece that makes an excellent point (similar to Peter Thiel) about the next wave of innovation being in the world of atoms versus the world of bits. The reality is that as the cost of building digital businesses falls to a fraction of its current level, companies simply won't have as much of a need for later stage growth capital. Venture as an asset class will need to reinvent itself as the paradigm that has persisted over the past 30 years unwinds just as returns normalize.