The Unit Economics of Corporate Venture Capital

A bottoms up approach to venture enabled corporate growth

Across industries, corporations are investing earlier in the life cycle of strategically aligned early stage companies.

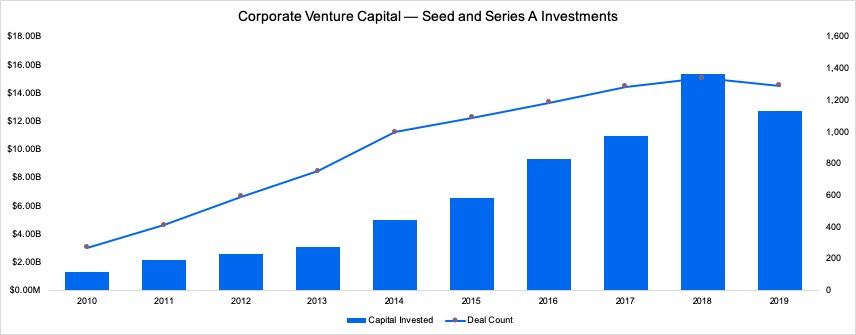

According to PitchBook data, the past decade has seen a significant increase in both the number of investments and the amount of capital deployed into early-stage (Seed and Series A) funding rounds by corporate backers.

And while 2019 saw activity and valuations cool off slightly, there remains more corporate capital than ever waiting to be deployed into early stage companies and willingness from corporate investors to push more money into individual companies at higher valuations than the prevailing market benchmarks.

In a market where the median CVC fund size has exceeded $75m every year since 2014 and the median assets under management (AUM) for active CVC units is edging towards $200m, a recent recommendation by 500 Startups — $50m as the minimum commitment required to build out a “useful” corporate venturing initiative — hardly seems like enough to make an impact.

As you continue reading through the post, I’d love to hear your thoughts in this thread on Twitter.

The Unit Economics of CVC

Perhaps counterintuitively in the face of rising competition, bigger funding rounds and higher valuations, companies pursuing a venture enabled growth strategy should start small. In fact, they should stay well below the “recommended” $50m and forego the grandiose announcements (i.e. executive ego-stroking) that often accompany the launch of new innovation initiatives.

The last few months have served as a stark reminder that pouring too much capital and hype on top of companies with shaky operational and cultural foundations can have disastrous consequences. The same “foie gras effect” applies for incumbents building out a corporate venturing capacity and inevitably leads to, as investor David Sacks recently put it, a focus on going from one to N before solving the right zero to one problems:

Trying to re-engineer the unit economics or culture of a business that is already operating at massive scale is brutally hard. Searching for the scalable model when you’re already at scale is a contradiction in terms.

A corporate venturing operation is a highly complex operation, constantly balancing the need to perform both strategically and financially while interacting with a wide range of stakeholders both inside and outside the company. As with any complex system, a scaled out corporate venturing unit must be built from the ground up.

Starting small aligns the venture organization with a corporate’s business units, enables a market-informed strategy to take root and prioritises a focus on developing the right “product” — all of which serve to create a solid foundation upon which to build a venture-enabled growth strategy that persists and drives value over the long term.

Play in the right strategic sandbox

Most corporations launching a new venture initiative aren’t Stripe or Airbnb and are instead turning to corporate venturing out of some degree of weakness — often the inability to internally develop new business models and technologies or exploit emerging market opportunities.

Companies generally launch corporate venturing groups when top-down strategic initiatives have failed to create a sustainable path to growth.

An oversized capital commitment risks compounding the negative effects of an already misguided strategy by bringing a top-down orientation to the corporate venture group’s strategy — few corporate boards would approve $100m without centralised agreement and control over how that capital was being spent.

This top-down approach inevitably leads to a venture “shopping list” that approaches the market far too narrowly. The strategy becomes too closely tied to the core business and not creative enough to capture value from emerging opportunities that fall outside what is readily understood by top brass.

Corporations should instead prioritise optionality and maximise venture ecosystem surface area by writing small “collaboration capital” checks to buy mindshare from a venture without overly committing the startup or the corporate to a confining development path.

Instead of determining investment size based primarily on ownership requirements or other similar financially-focused criteria, a corporation should write the smallest check possible that buys enough attention from the venture to enable the exploration of a strategic relationship.

This approach is advantageous to portfolio companies as well and corporations are often surprised to find that a $250k check goes just as far in establishing collaboration buy-in from a venture as a $1m check. This is because the optionality under this setup runs both ways — a failure to find a workable business development or technology partnership with the corporate investors doesn’t leave the startup with a zombie board member early in the lifecycle or challenging optics to overcome with follow on investors. Instead, the relationship has the space to develop organically with less top down pressure from either side.

Prioritize culture

One of the most destructive forces in corporations is “not invented here syndrome” — the institutional mindset that external partners are incapable of reaching a company’s standard while paradoxically believing that they represent a threat that should be avoided at all costs.

Oversizing a corporate venturing arm too early can make this cultural tension worse.

Committing too much capital to an unproven, externally focused initiative is often seen as an admission from the C-suite that internal teams aren’t capable of delivering on a company’s next phase of growth. This can create jealousy, distrust and an incentive for resistance.

A smaller starting point creates a lower-stakes environment for a corporate venturing arm to build trust with business units and develop a more collaborative and integrated approach to growing its capital base and stature in the broader organisation.

Focus on finding product-market fit

All this will set the scene for the core value proposition a strategic investor is supposed to bring to the table: post-investment collaboration.

Too much capital too early for a corporate venturing units causes stakeholders to view the input itself as the end game — the commitment of some large pool of capital is incorrectly viewed by decision-makers as evidence of innovation.

A smaller initial commitment combined with well-understood success metrics links growth strongly to internal cooperation. It helps develop ventures relationships that, to paraphrase Shopify Plus general manager Loren Padelford, “create happy portfolio companies, not contracted ones”.

In corporate venturing — like in company building — simply deploying more capital is never the core driver of sustainable success. Incumbents unable to grasp this will inevitably fail to build the crucial combination of strategic insight, cultural commitment and market reputation required to avoid irrelevance and build a strong platform for future growth.