Enablers vs. Growers

Why aligning incentives with your customers is key to capturing the value you create.

I co-wrote this essay with my friend Gonz Sanchez, who writes Seedtable and hosts the Seedtable Podcast. He is one of the most plugged in analysts of the European tech and venture ecosystem and his work has been incredibly valuable to me in getting up to speed on what is happening across the continent.

If you find this post valuable, we would love to have you share it with colleagues and friends and come discuss with us on Twitter.

Incentives drive the world.

Correctly aligned incentives make it possible for people to allocate their time and talents to the right pursuits. Over time, small differences in incentive structures are amplified through virtuous and vicious circles and end up locking in long term winners and losers.

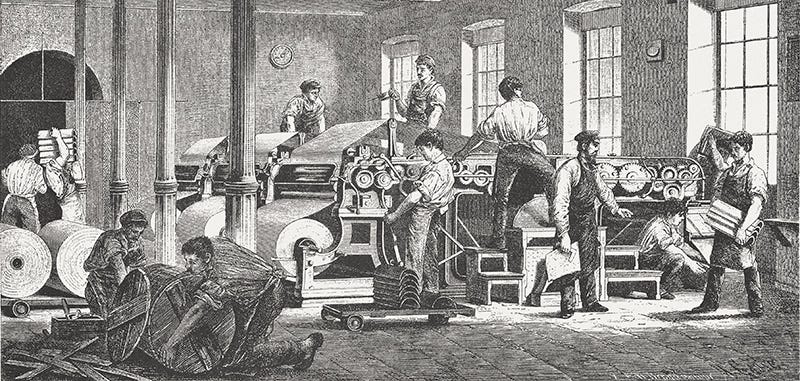

The Industrial Revolution in England was powered by "a fundamental reorganization of economic institutions in favor of innovators and entrepreneurs, based on the emergence of more secure and efficient property rights."¹

As improved property rights emerged, entrepreneurs and those backing them could be confident that new inventions, factories, and transportation infrastructure could no longer be seized arbitrarily. This incentivized all parties to invest time and capital in innovation, which spurred creative destruction and laid the groundwork for England's long term economic strength.

But incentives work backwards too.

Land redistribution and household farming were primary factors that propelled many Southeast Asian countries to prosperity. But in the Philippines, extractive institutional incentives stopped growth dead in its tracks.

Working capital had to be secured from informal lenders at 120% annual interest, the sole buyers were cronies who artificially deflated the end price, and the state offered no knowledge or support to increase yield per hectare to levels of similar countries.

The rational thing to do was to not work and “put 97% of their capital into a KTV machine and sing in a shack”². Either way, the lion's share of the profits would go to the landlord, moneylender, or merchant.

Just like in pre-industrial England or 1970s Philippines, incentive structures are highly deterministic in a business context. They align your business model, suggest how much value you should capture, and inform strategic & product decisions.

Incentive structures in business

One of the fundamental questions of incentive alignment that emerging companies must ask themselves is whether their primary relationship to their customers' growth is passive (“Enablers”) or active (“Growers”).

Enablers are companies whose purpose is to make it possible for other businesses to operate. The most successful enablers, like Stripe, often create the opportunity for entirely new business categories to emerge or cross the chasm.

Growers help their customers take the next step. With offerings and business models positioned to increase the value of their end customers, these companies often have the potential to capture the most value.

As companies like Stripe have shown, being a pure play enabler can be an incredible business. With a sufficiently large and complex market opportunity – like the Global Payments and Treasury Network – there are tens of billions of dollars of market value available for those who remain laser focused on laying down the rails.

But for emerging players seeking to compete with powerful enablers or incumbents reaching a competitive asymptote, becoming a Grower by playing an active role in expanding your customers’ footprint is the next frontier.

Moving from Enabler to Grower

There are three primary ways to move from Enabler to Grower:

Drive distribution to your customers by helping them generate new business that wouldn’t have been accessible otherwise (net new business). Shopify’s Shop App, which launched in part to combat competitive pressures from aggregators and product discovery engines is one example of this.

Facilitate business model evolution by adding upside to your customer's current business model. This is the approach Finix is taking as it seeks to break through in the highly competitive payments and financial services infrastructure market. Instead of offering payments to customers, Finix is turning its customers into payments companies and helping them turn what was a cost center into a revenue and growth opportunity.

Shift risk from the customer to the platform. Transactions often carry significant uncertainty so aligning financial incentives in a way that maximizes results and places the risk on the business is a fantastic way to disrupt incumbents. Companies powered by Income Share Agreements, like Lambda School and Placement, as well as iBuyers like OpenDoor or Zillow (an incumbent shifting from Enabler to Grower) fit into this category.

Not all of these paths are created equal and each comes with its own set of trade-offs.

Emerging companies unburdened by existing business models can take a more aligned approach but face the classic uphill battle of cutting through the noise and breaking down the accumulated accidents that define many markets.

Two such areas with deeply embedded status quo incentives are home ownership (OpenDoor) and higher education (Lambda School). As a result, breaking through requires new players to come to market with an offer that seems almost insane at first glance — a sight unseen instant offer on a house or tuition that costs nothing until you get a well-paying job.

Assuming risk that would have previously burdened customers shifts the incentives and allows emerging players (or incumbents with strong execution) to compete on an entirely different plane and capture significant value.

Harvard wouldn’t be Harvard if it admitted 1,000,000 students per year. Its business model is predicated on positional scarcity conferred from a limited number of seats at the table. The rational thing for colleges like Harvard is to focus on increasing the value of their credentials by artificially limiting the number of enrolled students.

Lambda School’s model, which assumes the risk of students finding a good job upon graduation (they charge 17% of salary, up to $30,000 total and only if you make more than $50,000/year), incentivizes them to serve the maximum number of students possible and invest in the success of said students. Otherwise they won’t get paid.

Substack and the blurry line between Enablers and Growers

For companies forced to make the Enabler to Grower shift to fend off competition, the incentives become a bit murkier.

Shopify’s Shop App, for example, puts the company at risk of becoming misaligned with their core SMB customers by playing the growth game.

Substack is positioned in this same foggy, risky zone between Enablers and Growers. And while the company’s revenue numbers are paltry, its influence on the media industry is growing and the tradeoffs it faces are common to any company navigating this incentive shift.

Substack is a true Enabler. The company provides the tools and infrastructure to help people start a paid email newsletter and they charge 10% of monthly revenue once writers start making money.

Structurally, incentives are perfectly aligned with the creators. If they don’t earn, Substack doesn’t earn.

But outside of the Top 25 charts on its homepage, Substack doesn’t actively participate in growing their writers’ audiences. Hosting your email list on their platform (versus, say, ConvertKit or Ghost) doesn’t give you a distribution edge.

The complication is that Substack is an Enabler but prices itself as a Grower – 10% of your revenue + Stripe fees – leaving room for new players to enter the market with a more aligned business model.

The reason Lambda School can charge 17% (!) of someone’s monthly salary is that they played an active role in securing said salary. The same could be said for the 10% that Placement charges or the 9% that goes to Pathrise.

Substack’s unclear situation exposes a weak spot that competitors can exploit and forces a potential strategic decision.

Their position in a nascent market is being jeopardized by their pricing structure. What prevents someone from copying Substack, charging 5% of revenue and taking market share? There is no doubt someone will eventually attempt this approach.

Substack has two options – lower commissions to align it with customers as an pure-play infrastructure layer Enabler or start dipping their toes in distribution, risk assumption, and end-customer business model evolution.

Recent announcements suggest they are going with the latter.

A few weeks ago the company launched the Defender Program to provide legal support for Substack writers. This is part of a bigger play that is made possible by aligned incentives. As an Enabler, Substack charges you nothing until you turn on subscriptions. From there, the company starts to assume significant risk on behalf of the creators on the platform — investments in education and training, legal support, a $100,000 fellowship, and dozens of $25,000 advances for new writers. Over time, if executed properly, we will likely see continued business model evolution offered to creators (native bundling, perhaps?).

If these expansions are well executed, Substack will move from high priced early mover with little revenue to the unbundler of traditional media it has been billed as.

From Substack to frameworks

The Enablers vs. Growers framework is a map you can use to make your own strategic and product decision and to understand where your competitors can attack you.

Some companies have well aligned business models already but placing themselves along the Enablers vs. Growers spectrum is a forcing function to analyze potential expansion possibilities.

In a world dominated by incentives, the more intelligently you can navigate the journey between enabling and growing your customers, the more value you can capture.

¹ Why Nations Fail, Daron Acemoglu & James A. Robinson

² How Asia Works, Joe Studwell

platform = enabler = facilitate the user task

aggregator = grower = replace the user task

over time anyone in between will either be wiped out or will be left to pickup scraps

Funny thing about that term "Enabler" is that in psychology that term is a pejorative that means a person who just enables another person to continue in their addiction.