How to Identify Underrated Markets

A framework for analyzing the catalysts of emergent demand

Extraordinary performance in venture capital hinges on the ability to identify overlooked and underrated opportunities in entirely new markets.

This requires, by definition, a significant divergence from the consensus perspective. Successful investors detach their thinking from the abstracted trends and third party narratives driving day to day capital and attention flows. They keep their eye fixed on the tactile reality of the game on the ground.

But resisting the urge to conform as peers and competitors move in the opposite direction is much easier said than done.

The Value of Predictions

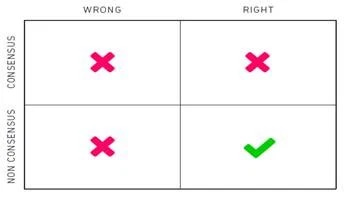

Howard Marks' 1993 letter to clients is the clearest articulation of the "non-consensus and right" framework he has become known for and provides a powerful look at the tradeoffs inherent in taking a non-consensus position.

In the letter, he writes:

The more a prediction of the future differs from the present, (1) the more likely it is to diverge from the consensus forecast, (2) the greater the profit would be if it's right, and (3) the harder it will be to believe and act on it.

Venture Capital is an exercise in funding a future that is radically different from the present.

But the feedback loops between the present and the future in venture capital are long and the opportunity costs associated with betting big on the wrong market opportunity (or not betting at all) can be significant.

These unique dynamics amplify the importance of identifying the right opportunities in the right markets.

Forecasting the Future

Whether we look to Marks or other investors like Seth Klarman and Benchmark's Peter Fenton, the lesson we can draw is that solving for the challenge of forecasting extremely different futures in new markets dominated by uncertainty is best done by anchoring on what is observable — "seeing the present clearly". Bottoms up instead of top down.

We can put this idea into practice by asking the following three questions about both markets and the companies within them to understand where underrated opportunities lie.

Does the audience skew "young"?

Is there a gap between engagement and monetization?

Are there artificial barriers holding back scale?

Understand the Demand

The distinction is subtle, but framing the evolution of a market in terms of what is happening (early engagement) and what could happen (catalysts) vs. what should happen (intellectualization) can help us see reality more clearly and build a framework for independent decision making.

1. Does the audience skew "young"?

Startups spend far too much time trying to convince investors that they are attacking massive markets. On the other side of the table, VCs shun anything that could be considered niche.

The reality, as Aaron Harris wrote, is that "many of the largest companies in the world started in markets so small they looked like toys." They also tend to start with what incumbents would consider to be the least attractive customers.

In some cases "young" speaks to the age of a company's early adopters and the way it designs its product to drive deep engagement and loyalty within that cohort — Snap's early user experience, which confounded older users, is a good example of this.

More broadly, this speaks to classic Christensen Disruption Theory.

The "youth" analogy holds well beyond consumer products. Over the last decade, companies like Slack, Stripe, and Carta built their initial go to market strategies around and scaled alongside the teenagers of the enterprise world: Startups.

Just like young consumers on Snap, startups as customers are (often rightly) considered flaky and cheap. They also represent the future, both in terms of how products will be used and where economic power will rest.

2. Is there a gap between engagement and monetization?

In underrated new markets, there is often a significant gap between engagement and revenue. This may be due to companies seeking scale in advance of monetization or, as explained above, because early adopters in the market are not particularly valuable or monetizable.

Facebook circa 2009 is a good representation of the value at stake for investors capable of developing a more nuanced, "know the knowable" perspective of how and when the monetization gap will close.

As it set out to raise its Series D round of funding, Facebook was in the process of recovering from the Global Financial Crisis that had slowed its growth and crushed advertising spend. But the company was consistently cash flow positive, growing revenue 70% year over year, and was still being valued by some Silicon Valley investors vying for the round at north of $5B.

What came next — outsider Yuri Milner and his firm DST leading the round at a $10B valuation — was one of the most impressive and lucrative investments in the history of venture capital.

Forgive the long pull quote but the entire story below, told by Marc Andreessen, provides an almost perfect description of the value accessible to investors who gain a unique perspective by being "on the ground" and reasoning with a view of the tactile reality of the situation at hand:

Yuri came through Silicon Valley in 2008 or 2009 for the first time, and he basically said ‘I’m in business and I want to invest.’ His first big deal was the Facebook deal. As you may recall what was happening in this timeframe: Facebook had printed an investment from Microsoft at a $15 billion valuation. Then the stuff hit the fan and there was a serious downdraft in valuations.

After the financial crisis, Facebook almost raised their next private financing round at $3 billion. Then there was a reset of the process, the economy started to recover a little bit and the process was re-run. Top American investors were bidding at the $5, $6 and $8 billion level for Facebook and Yuri came in at $10 billion. I was on the Facebook side of this and I had friends who were bidding on and I’d call them up to say ‘You guys are missing the boat, Yuri is bidding 10. You are going to lose this’ They basically said: ‘Crazy Russian. Dumb money. The world is coming to an end, this is insane.’

What Yuri had the advantage of at the time, which I got to see, was that Yuri and his team had done an incredibly sophisticated analysis. What they’d basically done is watch the development of consumer Internet business models since 2000 outside of the U.S., so they had these spreadsheets that were literally across 40 countries — like Hungary and Israel and Czechoslovakia and China — and then they had all of these social Internet companies and e-commerce companies that had turned into real businesses over the course of the decade but were completely ignored by U.S. investors.

What Yuri always said was that U.S. companies are soft because they can rely on venture capital, whereas if you go to Hungary you can’t rely on venture capital so the companies have to make money. So he had a complete matrix of all the business models across all of these countries and then came all of the monetization levels by user and then all adjusted for GDP.

Then, out at the bottom came: Therefore, Facebook will monetize at X. And his evaluation of what Facebook would monetize for was like four times higher than anybody else’s evaluation of what Facebook would monetize for. So he got the deal and has now made, now 24x on his $1 billion of capital in five years on the basis of superior analysis. To this day, I still greatly enjoy teasing my friends who missed that deal. He had the secret spreadsheet and you didn’t.

Immediately after the investment, Milner joined Mark Zuckerberg and TechCrunch founder Mike Arrington for an interview where he sheds additional light on the reasoning behind the Facebook investment that would go on to earn him billions.

3. Are there artificial barriers holding back scale?

As Facebook and other well-established tech companies have shown on multiple occasions, underrated growth markets and the companies within them often remain significantly underrated well beyond the point where they have reached major adoption.

This stems from the market's collective over indexing on the status quo and a failure to understand the on-the-ground catalysts that gradually (then suddenly) unwind and reshape the "accumulated accidents" that have locked in sub-optimal market dynamics, technological development, and cultural norms.

The idea of "Accumulated Accidents" originates with Clay Shirky and was recently explained in the context of growth investing by Dave Bujnowski of Baillie Gifford:

The idea of accumulated accidents challenges traditions and asks whether they really do represent an “ideal expression of society” (i.e. sacred institutions) or whether they are simply a series of accidents that can be unwound in the right circumstances. The unwinding part gets my attention because it often presents a significant new opportunity: Creative destruction in other words.

These accumulated accidents create artificial barriers to scale that are often overlooked by those analyzing new markets or operating within them.

On-Demand Audio – a common topic here on Venture Desktop — provides a useful example of how status quo market structures can create blind spots for investors not staying close enough to the situation on the ground.

In this market, the lack of innovation from early "winners" — Amazon in audiobooks, Apple with a failure to use its dominant position to advance RSS-based podcasting, and the record labels with their stranglehold on music rights — has created significant misalignment between the prevailing user experience & the job consumers want audio to fulfill for them.

This, in turn, creates significant opportunity for companies capable of identifying market misalignment and creating a wedge to begin unwinding the status quo-conferred market power of incumbent players.

Where to Look

Here are a few other quick ideas for markets and market opportunities that may be underrated in the context of this framework.

Video Games

It is hard to call a market with 2.7 billion participants and annual spend of over $150B underrated. But despite its scale, the gaming market has only recently “graduated” from a mass market social norm perspective beyond something kids do when they should be studying or playing sports.

Gaming is expanding its reach into every part of our lives (education, medicine, music) and is becoming the foremost battleground for the future of big tech. This strikes me as analogous to the Facebook story from above. The market clearly believes video games represent a valuable opportunity, but may be underrating the scale by orders of magnitude.

Micromobility

The narrative and hype cycle around shared micromobility has caused many to take their eye off the ball on the opportunity at hand. Huge scooter-centric funding rounds, blowups, and controversies distract from the fact that micromobility more generally is a classically disruptive technology platform and has the potential to transform cities in both the developed and developing world.

As cities in the developed world seek to unwind the accumulated accidents of car-centric planning and developing markets look to cope with congestion and pollution, micromobility will be critical in reshaping local commerce, transportation, and logistics.

And since I can’t resist playing Fantasy M&A, here are a couple of ideas for how micromobility will make an impact beyond just getting people from point A to point B.

Creator Economy

In recent years, we have been actively investing in the rise of what we call the “Professionalizing” Creator Class, a segment that has truly exploded during that time.

The growth of the podcasting ecosystem, the fragmentation of the online writing market, and the emergence of the “self actualization economy” provide a few examples where significant opportunities have opened up for companies building support infrastructure and distribution models to help emerging creators turn their passions and unique skills into careers.

I’ll let Li have the last word on the overlooked opportunity in this market:

Innovations in the Passion Economy represent new businesses that allow workers to compete against non-production. In turn, these workers can develop new products/services that serve previous non-consumers and over-served consumers. This means that across different industries, new Passion Economy platforms have the potential to disrupt incumbents.

Know the Knowable

Working backwards through this three question framework, we see that the breakdown of artificial barriers has the potential to serve as a catalyst for new emerging markets, vaulting them across the chasm to mass adoption and monetization.

As an investor, identifying how and when those radical chasm crossings will occur is not straightforward.

Gaining conviction around the artificial barriers that exist in certain markets is itself an exercise in non-consensus thinking given how deeply entrenched the status quo can be. Additionally, the forces that cause the breakdown of those barriers to scale come in many forms and interact in complex ways — from technological breakthroughs to societal and behavioral shifts to business model innovation.

To return to Marks, the only way to cope with such complexity and eventually capture the value that accrues to correct non-consensus positions is to anchor on the knowable:

Work in markets which are the subject of biases, in which non-economic motivations hold sway, and in which it is possible to obtain an advantage through hard work and superior insight.

Venture capital is a market rife with biases and non-economic motivations. Investors that stay close to the demand, eschew third party narrative, and ground their analysis in the tactile reality on the ground are best positioned to identify the underrated opportunities created by those market biases and profit from the value creation that radical futures are built upon.

If you enjoyed this post, I would love to have you share it with friends and colleagues or come discuss with me on Twitter.

Acknowledgements: Thank you to Leon Lin and Nathan Baschez for providing some helpful edits and ideas for this post!

Go Deeper

This post is an expansion on a number of other ideas and topics I have written about in the past. Here

The Merits of Bottoms Up Investing - Seth Klarman, Benchmark, and seeing the present clearly

Accumulated Accidents - Unwinding society’s suboptimal defaults

Economic Oceans - An earlier framework for understanding demand flows

You can also subscribe to receive my writing directly in your inbox. Thanks for your support!